“I honestly beleave it iz better tew know nothing than two know what ain’t so.”

[Original colloquial spelling]Billings (1874, p. 286)

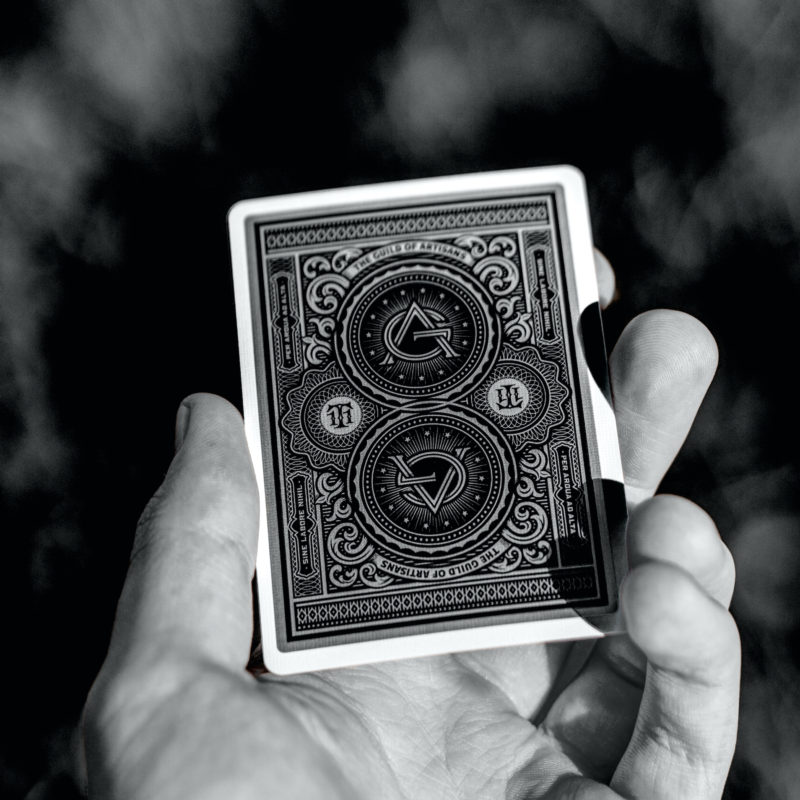

If one reads the websites of professional magicians, one soon encounters widespread claims of expertise in “deception”. Many magicians claim that they are a “Deception Expert”, a “Deceptionist”, a “Master Deceptionist” (presumably, somebody who has advanced beyond the level of mere “Deceptionist”?), a “Master of Deception”, a “Deception Artist”, or even a “Master of the Deceptive Arts”. They advertise shows with titles like “Deception”, “Beyond Deception”, “An Evening of Deception”, and “The Art of Deception”. And the association between magic and deception has been further perpetuated by the 2018 ABC show Deception, about a magician who is recruited by the FBI to work as a consulting illusionist, helping them to solve crimes.

Why is it that so many magicians claim to have expertise in deception as opposed to, say, magic? Are such claims valid? Have the performers who make these claims ever studied, or even considered, deception as a topic distinct from magic? Do they understand the relationship between magic and deception? And can they even define what deception is?

In a set of essays published in The Shift, an episodic series of magic books released by Ben Earl and Studio52Magic, I examine the relationship between deception and magic. In the first essay, A Ruse By Any Other Name, I lay a foundation for magicians to understand better what deception is, and how it functions within magic. By examining deception through the dual lenses of magic theory and magic practice, the essay provides a basis for magicians to reevaluate the conceptual basis of their work.

References

Billings, J. (1874). Everybody’s Friend or Josh Billing’s Encyclopedia and Proverbial Philosophy of Wit and Humor. Hartford, Connecticut: American Publishing Company.