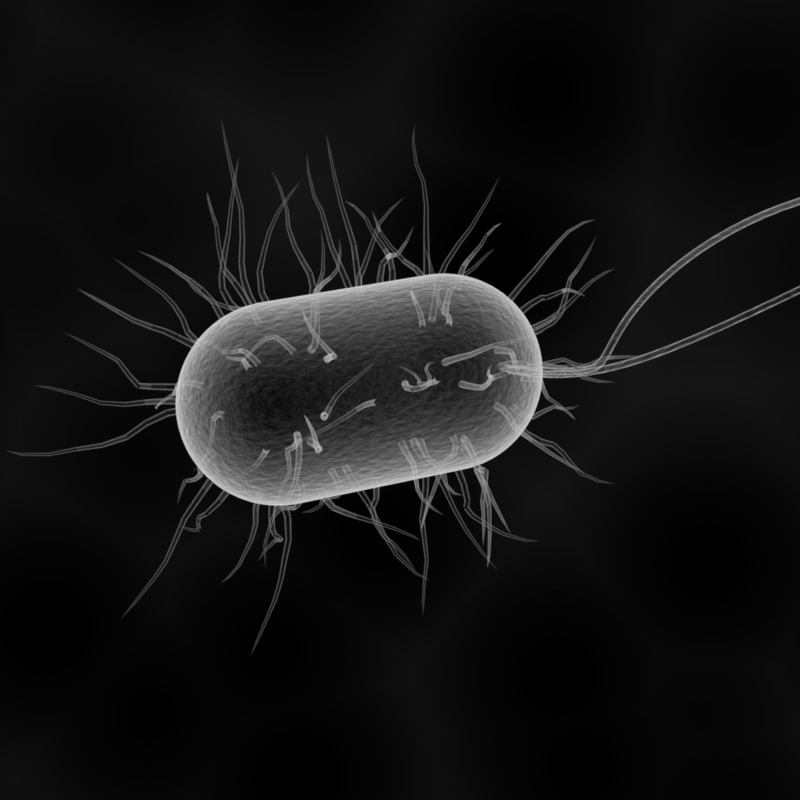

Deception exists throughout life. It occurs at all levels from the microbial to the geopolitical, and in every environment, including terrestrial, aquatic, and airborne settings. Bacteria employ molecular mimicry to trick their hosts into letting them enter cells so that they can survive long enough to reproduce. Plants use scent and visual mimicry to attract, predate on, and pollinate using insects, and employ a wide variety of different forms of deception, also for survival and reproduction. Deception is used by fish, reptiles, amphibians, arthropods, birds and mammals, with many different systems of deceptive signalling and behaviour that take place across a broad span of the electromagnetic spectrum. Children learn to lie at an early age, and the emergence of plausible lying is indicative that they are employing higher-level cognitive functions. Such functions include theory of mind (the ability to conceive the world from the perspective of others), and the construction of narrative (both skills that are fundamental to all human deception).

Deception can be found in almost every area of human endeavour, including advertising and marketing, archaeology, art, confidence tricks, fashion, forgery, fraud, gambling, health, intelligence, linguistics, magic, military deception, music, product packaging, politics, practical jokes, the psychic industry, science, social engineering, special effects, sport (as a legitimate tactic, and as cheating), theatre, and many other areas. Increasingly, deception is becoming highly prevalent in cyberspace, where humans fool humans, software fools humans, humans fool software and software fools other software.

Deception can be used malevolently, resulting in the target (i.e. the focus or object of the deception) suffering some form of disadvantage, such as a scam that steals their money. However, deception can also be used benevolently, where the target benefits from being deceived. Benevolent, pro-social deception occurs in art, comedy, drama, education, entertainment, fashion, beauty, make-up, gambling, magic, medicine, parenting, practical jokes, sport, storytelling & fiction, theatre, trompe l’oeil, visual effects, white lies, etc.

For example, in a pharmaceutical application, a foul-tasting and inedible cough mixture might be ‘repackaged’ using pleasant flavouring as a ‘wrapper’, so that the medicine becomes palatable and can be ingested by a patient to treat the symptoms of their cough. Interestingly, the deceptive strategies employed in all benevolent applications are precisely the same as those underpinning cases of malevolent deception. The dual potential of such strategies raises a range of important issues concerning the ethics of deception – a topic to be addressed in future postings.

From the partial selection of domains identified above, one can begin to appreciate the vast span of environments and forms in which deception occurs to create an advantage for the deceiver, and frequently for the target too. But does anything link together these different forms of deception? What are the common threads, and where are there differences? Later posts will address these issues.