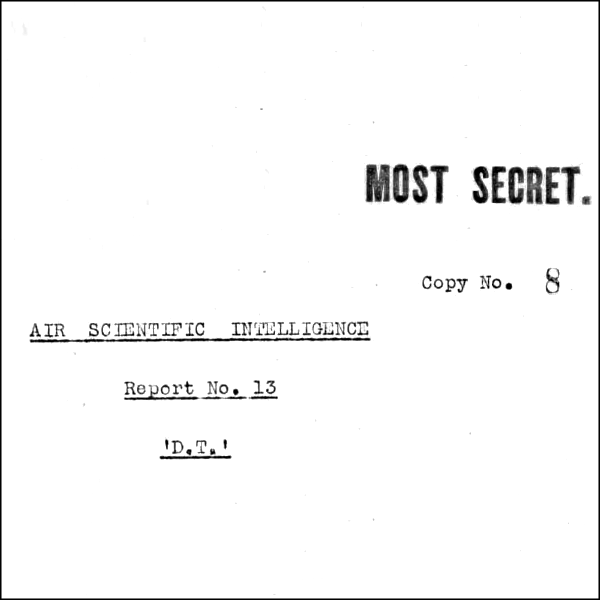

In 1942, British physicist Reginald Victor (R.V.) Jones wrote a report for the Air Scientific Intelligence Branch entitled Report No. 13: ‘D.T.’ (Jones, 1942). The report discussed vulnerabilities in German radar and was classified as ‘Most Secret’.

In Section 10.3.0, which discussed ‘Spoofing’, Jones highlighted a principle that has since become a bedrock of counter-deception theory:

“No imitation can be perfect without being the real thing.”

Deception and counter-deception literature quote this sentence widely. Some writers attribute the quotation to the original report, including Whaley & Busby (2002, p.197), Tan (2003), and Whaley (2007, p.101). Other writers (e.g., Bennett & Waltz, 2007, p.33) cite later books by Jones (Jones, 1978, p.287-289; Jones, 1989, p.131) that reference his original paper. And a few articles (e.g., Lawhead, 2012, and Segell, 2013) erroneously cite secondary sources (such as Whaley & Busby, 2002) as the quotation’s primary source.

Notably, some quotations end the sentence with an ellipsis (e.g., Whaley, 2016, p.52), suggesting that the sentence continues:

“No imitation can be perfect without being the real thing…”

Jones’s 1942 report is not available online. Indeed, it is not readily accessible anywhere. I, therefore, suggest that very few writers can ever have gone back, or have been able to go back, to read Jones’s original report. And I, too, am guilty of referencing this report without having read it (although, in my defence, I had previously read Jones’s discussion of his report in Jones, 1978).

Whenever possible, I always try to obtain a copy of all source documents I reference, including those from which I draw quotations. And as I was also curious about the context surrounding Jones’s quotation, I set out to track down a copy of the original 1942 report.

After an extensive search online, I could find nothing, save for a reference to a physical copy held at the UK National Archives in Kew, London. The Archive’s website revealed that no digital copy was available for purchase. Therefore, anybody who has read the original report can only have done so by visiting the Archives in person or by accessing another surviving copy.

To obtain a copy of the report, I first had to pay the National Archives £8.40 to check if the document was in a physical state that could withstand copying. Upon being informed that the document could be copied, I then had to pay a further £72.00 for an archivist to digitise the report.

A couple of weeks later, I received an email informing me that my order was “available for download”. However, clicking the included link took me to a page that contained 63 further links, each leading to a single JPG image corresponding to a page of the report. This arrangement necessitated downloading each image individually, combining the images into a single PDF, and then applying Optical Character Recognition (OCR) to make the PDF machine-readable.

The copying process used by the National Archives further suggests that nobody has ever previously requested a digital copy of Jones’s report!

And so, after considerable effort and many years of referencing the report without having read it, I now own a copy of Jones’s Report No. 13: ‘D.T.’.

And there it is, halfway down page 39 — the much-cited, often mis-referenced quotation.

Only, it turns out, there is a little more to it.

The complete sentence reads:

“No imitation can be perfect without being the real thing, but it is surprising what can be done by dexterous suggestion.”

The extra text explains the rare inclusion of the aforementioned ellipsis. The only other sources I can locate that include the complete sentence are Jones’s Most Secret War (1978, p.288), which includes an extract from the 1942 report; and Bennett & Waltz (2007, p.33), who attribute the quotation to Most Secret War.

The final (usually omitted) half of the sentence is critical. An imitation need not be perfect if suggestion can offset its imperfections.

I shall henceforth use the complete sentence in my publications. Or, at the very least, will signal its truncation with an ellipsis.

References

Bennett, M., & Waltz, E. (2007). Counterdeception: Principles and Applications for National Security. Artech House.

Jones, R. V. (1942). Report No.13. D.T. 10th January 1942. London: National Archives, National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists. AIR 14/3598.

Jones, R. V. (1978). Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence, 1939-1945. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Jones, R. V. (1989). Reflections on Intelligence. William Heinemann Ltd.

Lawhead, W. (2012). Seeing Is Not Believing: Insights for Intelligence Analysis from Professional Magicians. Workshop on Understanding and Improving Intelligence Analysis: Learning from other disciplines, 12-13 July, 2012, London.

Segell, G. (2013). Reflecting intelligence failures forty years since the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Retrieved 05/05/2022 from bit.ly/intelligencefailures

Tan, K. L. G. (2003). Confronting Cyberterrorism With Cyber Deception. Masters Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA.

Whaley, B., & Busby, J. (2002). Detecting Deception: Practice, Practitioners and Theory. In R. Godson & J. J. Wirtz (Eds.), Strategic Denial and Deception: The Twenty-First Century Challenge. Transaction Publishers. 181-221.

Whaley, B. (2007). Textbook of Political Military Counterdeception: Basic Principles & Methods. Foreign Denial & Deception Committee, National Intelligence Council, Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Whaley, B. (2016). Practise to deceive: learning curves of military deception planners. Naval Institute Press.