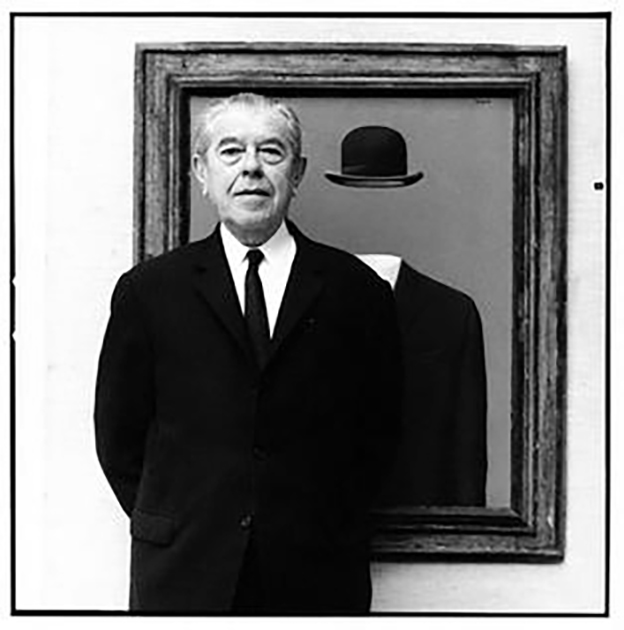

“Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see.”

René Magritte, (1965). Radio interview with Jean Neyens. In: Torczyner, H. (1979). Magritte: Ideas and Images. Trans. Richard Millen. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p.172.

Magic and Magritte

I recently attended a thought-provoking talk at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, by Dr Patricia Allmer, Senior Lecturer in the History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. Her talk, entitled ‘Magritte and Magic’, explored the influence of stage magic and conjuring on the work of surrealist artist René Magritte.

Allmer suggests that Magritte’s interest in magic coincided with the boom in theatrical magic performance around the turn of the 20th century. Magritte lived for part of his childhood near Place du Manège in Charleroi, Belgium. The city featured a permanent circus, a local cinema and several annual fairs and shows that would pass through the area. Magritte would have seen popular news and magazine articles featuring magic, posters featuring magic as part of the local circus shows and touring shows, and (Allmer proposes) Magritte may also have read books on magic.

Magritte spent a great deal of time skipping school and attending his local cinema, which he later painted in his work Cinéma Bleu (1925). Film director Georges Méliès, himself a performer and creator of magic, and at one time the owner of the Théâtre Robert-Houdin in Paris, is cited as having influenced strongly some of the imagery that featured in Magritte‘s paintings. For example, in Méliès’s film Un Homme de Têtes from 1898, multiple exposures are used to create the illusion of Méliès repeatedly removing his head and placing it on a table, a new head appearing each time on his shoulders. He finishes with three heads on tables, and a fourth on his shoulders, all of which join him in singing a song. Allmer suggests that Magritte may well have thought of this film and its title when painting his work Silence du Sourire (1928), in which four disembodied, near-identical heads float in space against a blue background.

Allmer notes that Magritte‘s paintings regularly feature objects from magic acts of the time, including boxes, cabinets, mirrors, doves, eggs, birdcages, skeletons, curtains, silks and drapes, hats, cages, frames, tables, umbrellas, roses, daggers, windows, screens, glasses of water, etc. Magritte‘s imagery also depicts vanishes and appearances (sometimes shown partway through the process), transformations, transpositions, levitations, optical illusions, manipulated perspectives, disembodied body parts, impossible objects, etc. The titles of some of his paintings (in English) include Daily Magic, The Magician, The Magician’s Accomplices, The Magic Mirror, The False Mirror, Black Magic, Attempting the Impossible, Time Transfixed, and Clairvoyance, etc.

Appearing to allude to magical principles, Magritte wrote that:

“the creation of new objects; the transformation of familiar objects; changing the constitution of certain objects: a sky made of wood, for example; the use of words with images; calling an image by the wrong name; putting into practice ideas suggested by friends; portraying certain visions of the half-awake state were, on the whole, ways to force objects to be sensational, at last… I was blamed for lots of… things and finally for showing objects in pictures in unfamiliar places. And yet, here, it is a question of making a real if unconscious desire come true. Indeed, the ordinary painter is already trying, with the limits fixed for him, to upset the order in which he always sees objects.” Magritte, R. (1938). La Ligne de Vie 1. In: René Magritte, Écrits Complets. Ed: André Blavier, (2001). Paris: Flammarion. P.109

Allmer finds further corroboration of magic’s influence on Magritte in the imagery from magic posters of the time. For instance, in Magritte’s painting Attempting the Impossible (1928), he presents an image of himself painting a woman into existence from thin air, an image potentially influenced by David Devant’s illusion The Artist’s Dream. In L’Évidence Éternelle (1930), a woman is depicted with her body spatially partitioned across several picture frames. Allmer suggests the image reflects the illusion of sawing a woman in half (although the image corresponds remarkably well with Chuck Jones’s later illusion from 1968, The Mismade Girl). In La Gâcheuse (1935), a young woman is shown with her head in a skeletal state (juxtaposing youth and death) which Allmer suggests corresponds with the 1915 poster, published by Waylandt and Bauschwitz, for the show Die Mysteriosen Catakomben. And in Homage to Mack Sennett (1936), a clothes cabinet’s open door reveals a partially inhabited dress, that Allmer proposes echos magic posters featuring spirit cabinets, such as Keller’s Perplexing Cabinet Mysteries and De Orm’s Marvellous Mysteries.

Allmer presents an interesting hypothesis. References to magic occur throughout Magritte’s formative years, and the sheer number of allusions to magic that then appear throughout his subsequent work makes for a compelling case. There is undoubtedly correspondence between Magritte’s work and imagery inherent in magic, although some of the examples cited by Allmer do rely on a fair degree of interpretive leeway. Unfortunately, there appears to be no direct evidence that Magritte ever studied or performed magic (although similarly, there is no evidence that he did not!). Magritte’s biographical legacy, and therefore his connection to magic, are further obfuscated by biographies about him that were written by friends, who incorporated fictionalised accounts of his life story (Allmer, 2019, p.12). Nonetheless, Allmer’s talk (and her book) provide fascinating insights into the impact of magic and conjuring on Magritte’s thinking, that serve only to deepen one’s appreciation for his work.

Artists have long explored and utilised magic and deception in their work, and there are innumerable connections between these fields. A few examples now follow.

Deception and Art

Deception and art are linked inextricably. Deception is as much an art as it is a science, and good deception often has an aesthetic quality to it. The productive and expressionistic realms of art also have countless connections to multiple forms and applications of deception:

- Deception is present in the gap between reality and representation, and is further amplified through the use of stylistic forms such as abstraction, expressionism, impressionism, surrealism, cubism, and many other approaches.

- Styles such as Trompe L’oile, Op Art, and Anamorphic Sculpture rely wholly on perceptual deception to achieve their effect.

- Many artists were involved directly in the development of military camouflage, including Norman Wilkinson, Joseph Gray, John Spencer-Churchill, László Moholy-Nagy, Roland Penrose, Frank Hinder, Abbott Thayer, Ellsworth Kelly, John Singer Sargent, and many others.

- Camouflage is a recurring theme within art and features in works by Andy Warhol, Peter Blake, Liu Bolin, Andrew Harvey, and many others. Camouflage has also been the subject of numerous dedicated gallery exhibitions.

- Magic and deception provide a focus for contemporary artists, such as Jonathan Allen and Tom Cassani.

- Deception underpins the subversive performance events staged by artists such as Banksy, The Yes Men, Harvey Stromberg, etc.

- Deception enables the rich and detailed design of immersive environments by theatrical companies such as Punchdrunk and You Me Bum Bum Train.

- Boundaries between reality and deception become blurred in the photo manipulation work of artists such as Christophe Gilbert and Riccardo Bagnoli, both of whom now produce art for advertising (itself a highly deceptive medium).

- The entire field of art forgery is rooted in deception, with some convicted ex-forgers now making a legitimate living selling ‘real forgeries’, such as John Myatt and Ken Perenyi.

This relationship between deception and art is symbiotic. Art depends upon, incorporates, and is influenced by deception. The practice of deception can (I would suggest, should, or even must) draw upon the ideas and techniques employed within art.

The (somewhat rare, and now often expensive) book, The Art Forger’s Handbook by Eric Hebborn, provides an excellent and detailed study of an artist’s approach to deceiving that can be applied readily in other domains. Its publication (to say nothing of Hebborn’s relationships with art historian, MI5 officer and Soviet spy, Anthony Blunt, and, later, the Mafia) is believed by many to have precipitated his murder in 1986. I would highly recommend Hebborn’s book to anybody seeking to develop a deeper appreciation of the art of deception, and indeed, the deception of art.

References

Allmer, P. (2019). Rene Magritte (Critical Lives). London: Reaktion Books.

Hebborn, E. (2004). The Art Forger’s Handbook. Woodstock, N.Y.: Overlook Press.